- Home

- Noel O'Reilly

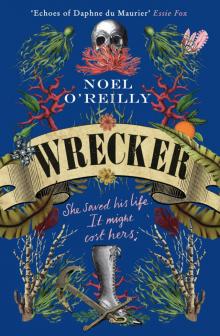

Wrecker Page 12

Wrecker Read online

Page 12

‘I wish you luck with it,’ said Mr Dabb, slurping his tea. ‘The mental darkness of these isolated villages is the shame of all Cornwall. We Methodists must work to subdue all degenerates who yield to the influence of wickedness. It’s our duty to show that a man may raise himself up through learning and sober application.’

Mrs Stone nodded her head heartily at this.

‘Let me tell you the problem with the country people, this young lady notwithstanding,’ said Mr Dabb. ‘It’s not want of employ, or short wages or dear provisions. The problem is the extravagance of the vulgar in the unnecessaries of life. Their children go about in rags, yet they think nothing of having three score snuff boxes in their homes. Alehouses contrive to let labourers live above their condition, crediting them till their account is so large that the bailiffs come after them, and the wretch must pay a fine as well as settle his scores.’

‘Surely we should look to the temper of the times in forming rules for conduct,’ Miss Vyvyan said.

But Mr Dabb would have none of this. ‘Take care that doling out funds to beggars doesn’t make them worse,’ he said. ‘Let them first show they are capable of fulfilling their moral duties and of showing a more correct feeling towards their superiors. When you make your trip to Miss Blight’s village, ladies, make sure that before giving alms to the country people you enquire into their character and habits.’

Just then, Mrs Gurney came in with a jug. ‘What am I to do with that girl! She plain forgot to bring the scalded cream,’ she said, putting the jug on the table. She stood behind Mrs Stone’s chair wiping her hands on her freshly laundered white pinny.

‘Surely Mr Dabb is right,’ said Mrs Stone. ‘The poor should save for their luxuries and pay their duties, just as respectable people do. And as for that ghoul in Porthmorvoren who chewed off a fine lady’s ears to steal her earrings . . .’

Miss Vyvyan was looking at me, which made me tremble, seeing in my mind’s eye the dead noblewoman lying on the sand. ‘Let’s not upset Mary, who I’m sure is as horrified as anybody about the crime,’ she said.

‘You know my feelings on the matter, Rebecca,’ said Mrs Stone. ‘When you catch the Porthmorvoren Cannibal, I hope you will make an example of him, Mr Dabb.’

‘P’raps it’s not my place to butt in,’ said Mrs Gurney. ‘But if it were up to me, that cannibal would get a salutary whipping, followed by transportation and twelve years hard labour. And that’s letting the varmint off lightly.’

I took a sip of my tea, but it had gone cold and bitter.

After three days had passed, my feet were healed enough to walk the mile to Penzance, so Mrs Stone and I set off to buy new boots. I was forced to wear the ill-fitting boots one last time, but it lifted my spirits a little to be out in the air after being pent up so long with the minister’s wife. The sky was bright with screeching gulls, and I could hear the cries of the merchants and fishermen down on the beach. A forest of masts could be seen where the boats were moored, the rigging clanking against the masts in the breeze. As we walked along the coast road, all of the bay opened out around me, and across the water I saw the castle set on a hill in the sea, and thought of Lady Rosemount in her castle in Italy.

Mrs Stone wanted me to know what a great sacrifice she was making, paying to have me reshod with brand-new boots. She hoped I didn’t think by it that she was well off. A minister’s salary was very modest indeed, she said. I let her talk wash over me while I enjoyed the light feeling that had settled on me that morning. A gang of Newlyn fishwives in scarlet cloaks came bounding past us. They carried their fish in their back baskets, which were tied to a broad band on their beaver hats, something I’d never seen in my own village. I feared they would be able to tell I was an enemy from Porthmorvoren just by the look of me, but they went past me without a glance.

Before long, we were climbing up Market Jew Street in Penzance through bustling crowds. I felt I could lose myself among so many souls. The different sounds thrilled my senses, the rattling of coach wheels and the clomping of hooves, the stallholders hollering, ‘Cotton, sixpence a yard!’ and ‘Shirt linen, only a shilling to you, madam!’ In the stores I saw gingerbread and hardbake, and candies of every colour under the sun, while other stores sold chapbooks and Bible prints, and I wished I could have bought the one that showed the animals lined up, two by two, before the Ark. We passed Moses and Son, conveyor of used clothes, a shop Tegen and I had been to in the past. Looking at the dresses hanging on the railings in the street, I had a giddy feeling that I could put on one of those garments and become somebody else altogether. Nobody would look strangely at me, or know or care who I was or where I’d come from.

On the broad, raised pavements, rich and poor rubbed shoulders, the better off in their fine coats and the poorer women in their worn and patched-up red cloaks. Behind the glass front of the draper’s shop there was a haughty wooden manikin, put there to show the latest fashions and what the establishment was capable of making. The manikin wore rich velvet mantles, and a dress that fitted tightly to the body. Underneath the bodice, the skirt fell in gathers, with crimped hems at the base.

But a moment later I was brought to a standstill by a notice nailed to a post. It was tattered and torn, but the words shouted out their message, and as I took in the meaning, the world reeled about me. I’d have fallen to the pavement had not a gentleman taken hold of my elbow. I stood there a moment, blood pumping in my ears and drowning out the noises of the street.

‘Miss Blight? Miss Blight? Whatever is the matter with you?’ said Mrs Stone, who had rushed to my side. ‘You look as if you’ve seen a ghost.’

‘If I might just sit a moment,’ I said, sitting down on the stone steps by the town hall. The words of the poster cast a shadow over me. A rich Lord was offering a reward, a huge sum, to any informer who would snitch on the evil-disposed person who’d robbed his wife’s boots and dress and jewellery, not to mention other foul deeds done on her person. The foulest deed of all was chewing off her earlobes to steal her earrings. In my mind’s eye I saw the bloody jagged edges of the lady’s ears, and saw Aunt Madgie stalking through the mist. I heard the old dame’s voice, Is this your doing, Mary Blight?

‘You do realise this is most inconvenient?’ said Mrs Stone, jolting me back to the here and now.

‘I’m sorry, ma’am. Really I am.’

A kindly woman handed me a cup of water, and I took it and sipped. Slowly I recovered, and became aware once more of all the folk going about their business. The lightheartedness I’d felt before had gone, and in its place a heaviness weighed on me. I watched the snots parade by in their finery, holding their breath so they wouldn’t have to smell the stale sweat of the poor people, or see the ragged hems of their skirts or trousers as they shuffled past. And I no longer believed I could escape into the crowd. The collar of my own dress was stiff with sweat from all the times I’d worn it before, and it rubbed against my neck. Under my skirts, the coarse worsted of well-darned stockings made my limbs itch. But even as the wretchedness of my life chafed with me, I told myself that all that mattered was to hide from danger, to stay safe and accept my lot.

I got to my feet and looked around for Mrs Stone, but I couldn’t see her in the street or on the steps. Then I looked back towards the post with the reward bill pinned to it, and there I found her standing before it, her nose inches from the printed words, the corners of her mouth turned down in disgust.

Shortly after, as I sat in the shop with bare feet waiting for the cobbler to find some second-hand boots that fit me, Mrs Stone picked up my ill-fitting boots from the floor, and looked them over closely. She frowned and mouthed some words, her voice so soft I had to read her lips: ‘Half-boots laced before . . .’

‘I’ll hold onto these boots,’ she said. ‘I’m sure Miss Vyvyan and I can find a deserving woman to donate them to on our next tour of the parish.’

‘I was hoping to pawn them, myself,’ I said.

‘Given that I’m purchasing a

pair of boots for you out of my meagre housekeeping money, the least you can do is allow me to pass these on to someone whose feet they actually fit.’

With that, she asked the shopkeeper to parcel up the boots for her so she could take them home.

10

The next day Mrs Stone was barely an hour into her lesson when Susan came into the parlour with an envelope for her. She got to her feet, took a penknife from a drawer in her corner cupboard, prised open the envelope and took out a card. Whatever was written upon it made her turn pale and start tapping the card against her palm. She read it a second time, but must have found it no more to her liking because, without a word, she put it down and swept out of the room. I heard her footsteps on the stairs and a door slam shut upstairs. After waiting a short while, I crept over to the cupboard and picked up the card. On one side, these words were written in a fancy swirling hand:

To Mr and Mrs Gideon Stone, and Miss Mary Blight

and on the other it said:

Mr Jonathan and Miss Rebecca Vyvyan

Request the pleasure of your company for dinner

Seven p.m. on Friday, June 10th

Orchard Lodge

Belle Vue

Newlyn

What a flap those words put me into! I was jittery enough as it was after seeing the reward poster in Penzance, and now I would have to suffer a lot of snots gawping at me for a whole evening. Mrs Stone was sorely put out that I’d been made invited, it was plain, and she’d be colder than ever with me after this. But at least it meant Gideon would be coming back to Newlyn and I might find out why he had taken himself abroad.

How slowly the hours passed that day and the following. Mrs Stone was more scornful of me than ever as she worked to drill the true sense of the gospels into my head. On the evening of the dinner party, she put on the blue silk dress she’d been wearing the night I arrived. I wore the same dress I’d been wearing all that day, a simple black one, faded with sweat patches under the armpits. Gideon left it until the last minute to come home, which put Mrs Stone in a foul temper. He was too late for his ablutions or to change out of his clothes, which were crumpled and dusty from the road. When she scolded him, he said the clothes he wore to do God’s work were good enough for the hosts of any grand dinner party.

The pair of them spoke not a word to each other as they climbed up the hill, me tagging behind them. I would have liked the walk better if my nerves had not been so frayed. The air was much sweeter up in the orchards than it was down in the cramped cluster of lanes where the Stones lived. Orchard Lodge had fine green gables, and was the biggest of the old manor houses that can be seen from the harbour.

Miss Vyvyan herself came to greet us at the door, and seemed not to notice the coldness between Gideon and his wife. I was surprised to see her in a black dress as plain as my own. She led us into the dining room which was big with a high ceiling. The other guests were in their places on the long table set for dinner. Dr Vyvyan sat at the head of the table and Miss Vyvyan led me to the other end so we could sit next to each other. How my heart soared when I learnt I was to sit between her and Gideon.

‘May I introduce Miss Blight,’ she said, as we took our seats. I looked quickly round the table at the smiling faces of these well-to-do snots. Miss Vyvyan told me their names, but I took none of it in. I tried to smile at each in turn, but I couldn’t look them in the eye. There were three ladies from her benevolent society on one side of the table, very grand women, and opposite them three physicians, which I learnt is a sort of doctor, who sat alongside their wives. With dread, I saw that Mr Josiah Dabb, the new Justice of the Peace who’d had been at Mrs Stone’s tea party, was next to Mrs Stone, right across the table from where I was to sit.

I hardly dared open my mouth in such company as it would show how common and stupid I was, so I stared down at the plate before me. There was a row of knives and forks on either side of the plate. I had no clue which I should pick up. Another smaller plate was set to one side with a bread roll on it and a knob of butter that was going runny. Three glasses on long stems were standing before each person. A young woman came and leant over my shoulder to pour some wine into one of the glasses. The wine was clear as water with bubbles rising in it. I took a gulp, grateful for the mellow, warming, tingling feeling that spread through me.

Miss Vyvyan spoke to me as if I was her equal. She told me about the work of the benevolent society, but I kept losing the thread with all that was going on about me and, most of all, because Gideon was next to me. Miss Vyvyan was not what people would call a handsome woman, but tall and thin, with big crooked teeth and a nose that was curved and sharp as a hawk’s. Even so, she seemed comely to me. When she turned to chat to Mrs Stone and Mr Dabb, I wondered if the minister would say something to me, but he did not. I didn’t suppose it was my place to speak to him, so I looked all about me at the room.

On one side there was a window that opened onto some grounds. It looked out into the bay far down below, where a broken path of moonlight danced on the water. Heavy, great, mustard-coloured drapes hung at the window, with velvet tie-backs. Over the fireplace was a large painting of a fine chestnut stallion. His haunches were painted so artfully I thought I could see the muscles rippling, and the horse’s long face looked so clever it wouldn’t have surprised me if he had opened his mouth and spoken in the King’s English. On either side of the fireplace were big, gloomy portraits, an old man and woman staring out of the sooty darkness in their black clothes and white collars. They had the likeness of Mr and Miss Vyvyan, so I thought they might be their dead parents.

Every wall was filled with shelves of old leather-bound books. It tired me to look at them. A handsome Turkish rug covered most of the floor, frayed in places, and there were fine old chairs, all of them scuffed with wear. It puzzled me that while this house was far grander than the Stones’ little place, it was quite shabby, whereas in theirs everything was buffed up to a shine.

The food came, a thick, oily, orange-coloured soup with chunks of ox tail floating in it. I watched to see what spoon the others picked up, and followed after them, moving the spoon from the front of the bowl to the back and sipping from the side of the spoon. I was already better bred than Mr Dabb, for he sipped from the point of his spoon, bending low over the bowl and even slurping a little. I took bites from the bread roll but didn’t dare dip the bread in the soup as I would have done at home. With the slightest touch of my spoon, the flesh of the ox tail fell away from the bones and it was more tender than any meat I’d known. It was rich fare, though, and I wondered how I would ever find room for pudding.

Down the table from me, the doctors were talking about whatever dull things such gentlemen discuss, and their wives, thank the Lord, were too far away to bother with me. Miss Vyvyan was talking to the minister about the business of the Newlyn Methodist Society, and asking him about his hopes for the new chapel in Porthmorvoren. He said little, and I noticed his hand go to his mouth now and then to hide a yawn.

Miss Vyvyan turned to Mrs Stone. ‘We are neighbours in Newlyn, aren’t we, my dear?’ she said. She caught the eye of her philanthropical ladies. ‘Ellie lives in a charming house in the lanes by the harbour, which she maintains in perfect order, while I am a dreadful sloven,’ she told them.

‘Oh, it is only a modest property,’ Mrs Stone said. ‘I must confess that when we first went to look it over, I was disappointed to find it so small and plain. But as the wife of a minister one must learn to want no more than will suffice and make that little do, and put what is committed to your care to the best advantage.’

Gideon sighed when he heard this.

‘You are a veritable saint, Ellie,’ said Miss Vyvyan, giving Mrs Stone’s hand a squeeze.

Across the table, Mrs Stone turned to chatter with Mr Dabb. Her twinkling that night was the brightest I’d yet seen. I looked to see how the minister felt about his wife’s flightiness, but he just stared, heavy-lidded, at his soup, which he’d hardly touched.

&n

bsp; Mr Dabb’s voice was too loud to ignore. ‘Not long ago I sent a man from Lansallos to the assizes for stealing a watch, and when the jury found him guilty the judge sentenced the poor wretch to death,’ he told Mrs Stone. ‘Nor was this the first occasion that I’ve encountered such harsh treatment in my time on the bench.’

‘I wonder if I would know any of the offenders by name?’ asked Mrs Stone.

The serving girls arrived to take away our soup bowls. Then, to my amazement, they brought in two large joints of beef and put them down at either end of the table. Dr Vyvyan got up and began carving one joint and putting bits onto people’s plates, while at our end one of the doctors did the same. The girls then brought pickles and jellies, and trays of potatoes, carrots and sparrow grass, enough to feed a family in the village for a month of Sundays. For a while, all were quiet as they cut and chewed their beef. I could manage only a slice or two. The meat got stuck in my teeth, but I thought it would show bad manners to get the gristle out with my fingernail. I noticed Mr Dabb had no such qualms.

With a jolt, I realised Gideon was speaking to me, his head bent towards me and his voice low so that only I would hear. ‘I trust this is not too much of an imposition,’ he said.

‘It’s no trouble. I have never eaten so well.’

‘Well, don’t grow too accustomed to it, Sister Blight. I wouldn’t want you spoilt by luxury, like these people.’ He looked at his wife as he spoke.

Just then, one of the philanthropical ladies called to me: ‘Miss Blight, won’t you tell us about your famous cove?’

‘Infamous cove, more like,’ said Mr Dabb.

All of them had turned to face me, waiting to hear what I would say, but every thought flew out of my head. Staring into my lap like a half-wit, I felt a bead of cold sweat roll down my neck and under my collar.

‘If it wasn’t for Mary, Gideon wouldn’t be here today,’ said Miss Vyvyan. ‘She rescued him from the sea, at great risk to herself.’

Wrecker

Wrecker