- Home

- Noel O'Reilly

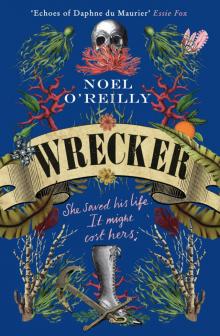

Wrecker Page 15

Wrecker Read online

Page 15

I was in such a passion I couldn’t trust myself to speak, so I pushed past her and almost ran into the lane. Before I had turned the corner into Downlong Row, she called after me, ‘Mind that every word you teach them is sound Bible doctrine, young lady!’

13

Five bleeding wounds He bears,

Received on Calvary;

They pour effectual prayers;

They strongly speak for me.

Forgive him, O forgive, they cry,

Nor let that ransomed sinner die!

The sound of women’s voices singing ‘Arise, My Soul, Arise!’ echoed around the cove for all to hear, as a bunch of us womenfolk climbed the hill out of the village. Gideon walked before, blending his deeper voice with ours, as we followed him to the kiddlywink. There was me and Tegen, and Cissie Olds, the Widow Chegwidden and Martha Tregaskis. Halfway up the hill, Nancy Spargo joined us, her big arms swinging at her sides, along with a couple of her mates from the tinners’ cottages, both as stout as she.

The journey came about because Gideon had asked for hearers to come forward to make a deputation to visit the kiddlywink. ‘My work here will not be accomplished until I have brought the vilest class of sinners under conviction,’ he told us. We were to go and persuade the ruffians who loafed about in that filthy shack to choose temperance and go home to their wives and children. I put my hand up quicker than any to enlist, for this was a chance to be near the minister. He had kept well out of my way since he’d given me Mr Wesley’s hymn. But I had little faith that our visit to the kiddlywink would make the men who drank there into God-fearing Christians.

We were still singing, although more raggedly, when we reached a blighted orchard of dry and twisted trees, where only a few hardy sea cabbages and silver ragwort had taken root, together with tangled shoots more suited to the ocean bed that had wound themselves around the tree trunks. Beyond this was the lane where the miners lived, two rows of cottages facing each other across a narrow lane that the sun’s rays never reached. A couple of children scampered ahead of us and disappeared from sight. We found them in a narrow alley between two cottages, shadowy figures lurking in the gloom. The minister stood at the entrance to the alley, seeming much troubled by what he saw.

‘They are brother and sister,’ I said, as I pushed my way through the women to stand at his side.

‘A most distressing sight. How did the boy lose his hands?’

‘It was when he was an infant. His mother nipped out to fetch something and forgot and left the door open. The family pig got in and his Mamm couldn’t pull the animal off in time.’

‘Oh, but it’s a blessing in disguise, really,’ said Martha, squeezing herself between me and the minister. She stank of liquor. ‘The little scarper will never have to work, and his father have made a fair wack showing him at fairs and markets.’

Gideon stared, frowning, at the boy’s sister, whose face was badly pock-marked.

‘Smallpox, minister,’ said Martha. She lowered her voice to a whisper. ‘It’s been visited on the child because someone in the family have angered God.’

Gideon shook his head, and sighed heavily. ‘She is an innocent child, Martha. How will I ever break the chains of superstition and barbarous custom that bind you people?’

We moved on and before long, we were within reach of the kiddlywink. The tap boy came running out. ‘You can’t come in here. Women ain’t allowed. Now get on home, or else!’

‘Out of the way, scrimp!’ said Nancy, bowling him over onto his ass. With the minister in the lead, we filed into the shack. In the airless hovel, it was too dark to see at first. The fusty smell of the men’s clothing and the reek of sweat, tobacco and strong liquor were hard to stomach. One of the women had a coughing fit. When my eyes grew used to the light, I saw perhaps a dozen men through a dense haze of tobacco smoke. Several of them had got to their feet and stood there, gawping at us women in disbelief. Others perched on piles of brick or on empty ale firkins, staring at us, looking none too pleased. One fellow lay passed out on the floor behind the barrels, only his legs showing. A group sitting around a tub were frozen in the midst of a card game, one fellow’s hand hanging in the air at the point of throwing his card down on the table. Piles of coins lay on the barrel. One huge fellow sat with his back to us, and there was no mistaking that bald, misshapen head and those broad shoulders – it was the giant, Pentecost, the husband of Martha Tregaskis, who was cowering behind the other women.

Gideon took a step forward, stooping to miss a low beam with hops hanging from it. He took up a place by a row of barrels, and cleared his throat. ‘Gentlemen, may I have your attention!’ he called.

‘F— off out of here!’ shouted Pentecost.

‘You has a nerve coming here, parson,’ said another fellow. It was Ethan Carbis, who sat in the middle of the hovel, his pipe held to his mouth. He wore a filthy sacking apron smeared with dried blood. ‘Can’t an honest working man enjoy a quiet drink with his associates without being pestered by Bible thumpers?’

‘As I have yet to see any of you gentlemen in attendance at our prayer meetings, I thought I would come along and invite you to worship with your neighbours,’ said the minister. Some of the men shook their heads with disbelief.

‘I has a mind to swing by one of these nights. I hear it’s full of women,’ said Ethan, which made them all laugh.

‘Your missus would have something to say about that,’ said Nancy.

‘She can go hang,’ said Ethan. ‘You know how it is, parson. Us men forget the wedding vows when the first storm of fervour have died down. You got a missus yourself, I heard, so you get my meaning.’ He winked at the minister. ‘A man needs a few pots of ale of an afternoon to get through the marriage scrimmage with no tiles off the roof.’

‘It’s the custom hereabouts for a stranger to stand a drink for one and all,’ said Ephraim Lavin, the blind fiddler. He had his fiddle on his lap and no doubt he came to this filthy place to play airs, hoping the drinkers would throw him a few coins. He sat with his back against one of the barrels that were stacked at one end of the room, and his cloudy yellow eyeballs looked out at nothing in particular.

‘I’m afraid I must disappoint you, then,’ said Gideon. ‘My purpose in coming here is to persuade you to take a pledge of temperance.’

‘Go to hell, then!’ said Ephraim, raising his pot for the tap boy to take away and fill. ‘Here’s a health to the barley mow!’

‘Since you has showed yourself to be a sportin’ man, parson,’ said Jake Spargo, ‘why not make a wager tonight? I has the pluckiest devil of a rooster, and you can watch him flay the life out of Henry Trenhouse’s cock. As guest of honour I’ll save you a place in the front row. You’ll be liberally sprayed with blood, I promise you.’

‘Take no notice of him, parson,’ said Nancy, glaring at Jake, her husband. ‘He’ll get a piece of my mind when he gets home tonight, never you fear.’

‘I might come home more often if she was less of a scold,’ muttered Jake.

Gideon spoke. ‘I came here this evening, as you gentlemen well know, to speak out against cock fighting, and against wrestling, and against every species of barbarity that plagues this village. Against wrecking and smuggling, breach of the Sabbath, intemperance, gambling and above all against disrespect toward women folk. My work here will not be finished until I have brought the better men among you under conviction.’

‘Any more sermonising from you, rector, and I’ll give you syphilis of the mouth,’ said Pentecost, looking over his shoulder as he slammed a playing card down on the barrel in front of him. The women were in uproar at him using such lewdness with ladies present, but his mates only laughed.

Ethan puffed on his pipe. ‘It do seem to I, parson, that your doctrine is hard on poor men like we, whose only pleasure in life is to partake of a pot or two of porter with our mates every once in a while. From what I hear, King George himself is fat as a hog from gorging on cake and sherry. And he keeps a harlot round the corner for

his own convenience.’ He blew a long stream of smoke up into Gideon’s face. ‘There be one rule for the bettermost and another for the poor, I reckon. And a word of advice to you, parson: we men here take great offence at you calling us “wreckers”. We ain’t wreckers; we’re salvors.’

‘If the goods you plunder are salvage, then why do I see them on sale in Penzance?’ asked Gideon.

‘That be the King’s fault, I seem. It were he that put duties on every basic necessity, just so he could service his debts from the French wars. The King’s Coast Guard would rather sink a ton of tea than let we poor folk enjoy a drop of it. And we has scarcely salt enough to cure our pilchards. You can forget your Methody notions, parson. They don’t take hereabouts. You ain’t in Newlyn now.’

‘They Newlyn women is all whores,’ said Davey Combelleck, who was one of the card players. ‘Exceptin’ your good wife, of course, parson.’

‘Newlyn is the Home of Sin,’ said Ethan. ‘A fact which admits of no gainsaying. They Newlyn wenches is only half human. They has poison in their spit so when you kiss them you lose your senses and are helpless to stop ’em dragging you down off the quay to drown you.’ He stooped towards the spittoon, and his phlegm rang on the metal like a pellet. ‘It’s a matter of common knowledge that they Newlyn women can make babes all by themselves, without need of a man at all.’

‘Your conversions hereabouts has been mostly among the women folk, if I ben’t mistook,’ said Jake, looking slyly at the minister.

‘Show some respect, you dirty stop-out!’ said Nancy, wagging a finger at him.

‘It don’t belong to women to go out nights to prayer meetings when they should be at home taking care of the childer, and that’s the gospel truth,’ said Jake in a wheedling, self-pitying voice.

‘Did Christ die on the cross to save the likes of you men? Shame on you!’ said Gideon. As he spoke, I saw Pentecost get to his feet and turn to look at him. The big oaf loomed out of the smoky haze, his eyes no more than tiny hollows, his face hewn out of granite, his nose broken in at least two places and his great slab of a chin jutting before him, deeply dimpled. At the sight of him, Martha, who had the bad luck to be his wife, tried to hide herself behind the other women.

‘Come out here,’ he shouted at her. She made a bolt for the door, but he stopped her with another yell. ‘I’m speaking to you. Come over here this minute, or I’ll show master and lay on you so hard you’ll wish yourself dead – and I don’t care who sees it.’ Martha turned and pushed her way through the women to stand in front of her husband, clutching herself and not daring to look up at him. ‘What are you doing here, you slack old lump of misery? You want to shame me in front of my pals, do you?’

‘I am come with the minister.’ Her voice was so soft it could barely be heard.

‘That’s right, you’re here with me, Martha,’ said Gideon, putting his hand around her shoulder.

‘To tell us to stop drinking? Is that why?’ Pentecost said to Martha.

First she shook her head, but then she looked up at Gideon and nodded.

‘You come here stinking of liquor and has the nerve to tell me to stop drinking?’ said Pentecost. ‘Go home, before I break your neck.’

She shook her head, and muttered, ‘I can’t, Pent. We’ve come to ask you men to come home to your wives.’

‘What is this? A mutiny?’ He took hold of her arm.

‘Don’t you be hurting me! Not in front of my friends,’ she cried. ‘Please, Penty!’

‘I’ll show you hurting!’ The back of his hand struck her hard across the face, and every woman in the alehouse screamed. Martha would have fallen if Pentecost hadn’t held her up, gripping her by the arm. Cissie Olds and the Widow Chegwidden tried to pull Martha away from him. She was panting, her head thrown back and blood pouring thick from her nose. There were red specks over Cissie’s apron.

Gideon stepped right in front of Pentecost, looking up into the giant’s eyes. ‘I warn you not to lay another finger on this woman!’ he said.

‘What’s this world coming to if a man can’t beat his own wife without a ranting preacher getting in the way?’ said Pentecost, with a sneer. He let go of Martha and turned to walk away, but then quick as lightning threw a punch that caught Martha in the ribs. Nancy leapt on the brute’s back and tried to pull him away, shouting, ‘Leave her be, you dirty bullswizzle!’ But he shrugged her off, and she fell heavily to the floor, groaning. Everything was happening at once. Martha was bent double, making sounds like a wounded animal. Gideon was grappling with Pentecost, and barrels were overturned. The women scattered to get out of the way, the men rose to their feet, and somewhere in all this Martha fell to the floor.

Pentecost held Gideon in a bear hug, and pushed him up against a wall, making the whole hut shudder. ‘Come outside, milksop, and show me what you’re made of,’ he taunted. ‘Let me get you in a hitch and make a man of you. I’ll learn you a few throws, the foreheep, or the flying mare, maybe.’ With a sudden lunge he got Gideon’s arm twisted behind his back and his head locked in the crook of his arm. He began banging Gideon’s head against the wall, making dents in the cob. I ran over, and tried to pull him off, hearing my own voice as though it were somebody else’s. ‘Leave off, you devil, let him be!’ I near tore the shirt off Pentecost’s back but to no avail, so I reached around him to grab hold of his face, and tried to dig my nails into his eyes. He shook his head and let go of Gideon, who fell in a heap on the floor. Then he turned around and stood there, opening and shutting his eyes one by one to see if he could still see through them. There were scratches on his brow and cheek.

‘Which one of you bitches did this?’ Pentecost looked around at us, one eye shut and the other squinting, and every woman looked down at her feet. I was the nearest to him, and he peered at me through the little slit of his good eye for a while, sweat dripping off the end of his nose. ‘You’ll pay for this, whichever one of you it was. I’ll find out.’ Then he stomped out of the shack, leaving his wife lying on the floor, her hair caked in her own blood. The women crouched down by her.

I rushed to Gideon and got down on my knees by him. ‘Let me have a look at you,’ I cried, taking his head in my hands. I could feel a big bump under his scalp, but saw no blood. I helped him to his feet, and he looked around, dazed, touching the top of his head and wincing. His gaze alighted upon Martha lying on the floor, with Sarah Keigwin and Tegen squatting down beside her. He went and stooped over Martha, looking at her nose, which was purple and swollen.

‘Will one of you take in Martha tonight?’ he said, standing upright. ‘She shouldn’t go home after this, not until I’ve had words with that bully.’

‘I will take her in,’ said the Widow Chegwidden. ‘I have remedies that will comfort the poor creature.’

‘And I will look in on her children,’ said Cissie.

Gideon looked around the room, swaying, so I took his arm, worried he might swoon. He squinted at the men, as if puzzled to find himself among them.

A voice was heard, one I knew very well: ‘So this is the lay of the land.’ It was Johnenry’s voice. He stepped out of the gloom and staggered towards where I stood alongside Gideon. Johnenry was greatly changed since last I saw him, his face gaunt and smeared with dirt, one of his eyes black and bloodshot. I realised it had been him I’d seen before, lain out cold behind the barrels.

‘Such a big brave fellow,’ he said, sneering at Gideon. ‘I suppose Mary thinks you a proper snot with your fine words and foreign ways.’

‘Do I know you?’ Gideon asked.

‘No, but I know you well enough,’ said Johnenry. ‘Look at the pair of you, arm in arm.’

‘Come, we should get out of here,’ I said, tugging Gideon’s arm, but he stood his ground.

‘Who is this fellow?’ Gideon asked me.

‘It’s of no matter,’ I said.

‘No matter, say you?’ said Johnenry, glaring at me. ‘I be naught to you, then.’ He turned to Gideon. ‘What are you doi

ng by her, preacher man? You want to watch your step with this one, I tell you. You think you know Mary, but you don’t. Not like I do. Look at you! You be mazed by her, same as I were.’

‘Take no notice of him,’ I said, pulling Gideon towards the door, before Johnenry could say more.

‘We should speak another time,’ the minister called to him, over his shoulder.

‘Save your breath, parson,’ said Johnenry. ‘I don’t want to hear your measly sermons. King Jesus and all the Angels can go to hell for all I care, but if you hurt Mary I’ll make you sure you pay for it.’

I got Gideon outside. The Widow Chegwidden and Cissie were a good way down the hill, helping Martha home, with a straggle of other women in tow. The fresh air seemed to go to Gideon’s head, for he was staggering sidelong in one direction and then the other, as if the world was tipping up and down beneath him.

‘I’ll never get in a boat again,’ he cried.

‘Nobody’s putting you in a boat,’ I said, gripping his arm to stop him falling on his face.

‘I won’t go near water, mark you! I’d walk through hellfire first.’ He groaned loudly and clutched his head. ‘Such a pressing on my skull. And these lights. Is it glow worms out early to torment me?’

‘You’re muzzy, is all. You’ve taken a few blows to the head. Or don’t you remember what’s just befallen you.’

He stopped in his tracks, shaking his head. ‘I hit my head on the barrel out there on the swell,’ he said.

‘That was months back. We’ve just been in the kiddlywink, not five minutes ago. That brute Pentecost took hold of you and banged your poor head against the wall.’

‘That’s a damned lie! I’ve not set foot in an alehouse in ten years. No since . . .’

‘Have it your own way, then,’ I said, startled to hear an oath like that from him.

He reeled again, unsteady on his feet. I saw a boulder up ahead and pushed him towards it. ‘Look, sit yourself down here,’ I said, when we got there. ‘Sit quiet a while now. You’re dizzy. We’ll wait here till it wears off.’

Wrecker

Wrecker