- Home

- Noel O'Reilly

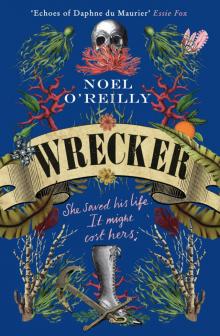

Wrecker Page 18

Wrecker Read online

Page 18

He turned from me and for a while stared down at the water churning underneath us.

‘I only wish what is best for you, Sister Blight,’ he said.

‘It’s no business of yours whom I wed,’ I said.

Before he could say more, I dashed over the bridge and turned up Downlong Row. He soon caught up with me and we stood face to face. Before he spoke, he glanced up and down the lane to make sure we weren’t spied upon.

‘I’m concerned that we may have had a less than perfect understanding in the past, and perhaps I’ve been at fault,’ he said. ‘I confess that I’ve had a nagging doubt about my advocacy of you as school mistress, but I have tried to examine my conscience.’

‘I’m pleased to hear it. Now, if you please, my basket’s heavy and I want to get home.’ I began rushing up the hill again.

‘Whatever I have done, it was done in your best interest,’ he said, coming alongside me.

‘Leave me alone! I’m weary of all your endless twaddle.’

‘Please, speak softly. Think how it will appear if we’re seen quarrelling. I can’t part from you until this is resolved.’

I stopped, reached down the front of my dress and, after a moment’s fumbling, found the scroll of paper that I kept on a string next to my heart. I pulled the string over my head and held Mr Wesley’s hymn before his face. ‘Why did you give me this?’ I asked.

‘Surely, you have not misread my intentions?’

I tore the page up and threw the scraps at him. ‘I think it best if we never set eyes on each other hereafter,’ I said. ‘Some madness has come over me these last months, but I’ve come to my senses at last.’

‘Give me a moment to explain. Please, Sister Blight . . . Mary. On reflection, it is possible, I suppose, that in asking you to reconcile yourself to that young man, I was trying to remove a doubt from my own mind. Perhaps I wanted to be sure that all I’ve done with regard to you has been undertaken with pure and proper motives.’

‘If you have no feelings for me, why won’t you just let me go?’

‘I can’t speak of this here in the lane. We could be overheard.’

‘Then go!’ I shouted.

He flinched, then leant over me to whisper in my ear. ‘As you give me no other option, I will attempt to explain my position. It is possible that a man might, in all sincerity, mistake religious fervour for . . .’

‘Louder, I can’t hear you aright!’

He shut his eyes and took a deep breath. ‘It is possible that a man might mistake religious fervour for strong affection of a quite different order, and that my thoughts in relation to yourself may have been acted upon by . . .’ He looked over his shoulder to make sure nobody was listening. ‘. . . Acted upon by a kind of unconscious propensity. As you insist on pressing me, I will admit to certain feelings for you.’

‘For God’s sake, say what you mean in plain words, Minister.’

He looked sorely vexed. ‘What I meant was that, yes, I do feel drawn towards you. But you must understand that everything has changed now that this, let’s say attachment, is apparent to us both. We cannot under any circumstances be seen alone together at a future time. It would be unforgiveable to put at risk the work that’s been done to establish a chapel in this cove. I am sure we are as one on this matter. A few months ago the old sickness threatened to overwhelm me, the despondency, the lethargy of spirit. I can’t risk backsliding.’

‘You can’t bear to think ill of yourself, can you?’ I said.

‘How can I forgive the unforgivable? Only Almighty God has that privilege, when Judgement Day comes. But if I’m to continue to do His work, I must have assurance.’

‘Perhaps if we were to lay out all the thoughts and deeds of any man from end to end, he would seem a hundred men,’ I said.

‘Then how are we to sort the wheat from the chaff?’

‘And what of me? What will I do? I have enemies in this village, and all the more so now that I’m school mistress.’

‘If you are ever in dire need, you may send notice to me. I’ll do whatever is in my power to assist. I give you my word. That much I owe you.’

He bowed, and went slowly back down the lane, his head hanging. But after only a few paces he stopped, and strode briskly back to where I stood.

‘From this point on, we must take every precaution. I think it would be best if you absented yourself from the Lovefeast. In fact, I would ask that from now on you attend only those prayer meetings that are led by Mr Hawkey. Will you promise me that?’

‘I will promise you nothing. What promise did you give those poor women you wronged?’

With that, I dashed back to the cottage. I charged upstairs and threw myself upon the bed. I was still lying there when it grew dark. A queer mix of feelings raged inside me. What was I to make of Gideon Stone? Wheat and chaff seemed all mixed up him. On the one hand, he was a soaring spirit who risked life and limb to save the souls of his fellow men. But in the shadows of his past lurked another man, a frail sinner, lost in drink and unable to master his base urges. He was either saint or sinner with naught in between. Couldn’t he content himself with trying to be a good man, as best he could, without wanting to be an angel on high? A man like dear honest Nathaniel Nancarrow, who Tegen loved with all her heart.

Yet, I had nobody else I could depend upon, if my neighbours ever took against me. As the hours passed, I came to see that what troubled me most lay deeper in the darkness of my own heart, and I trembled to bring it to light. When first I knew Gideon, I’d thought him a man set firmly on a straight course, who wouldn’t easily unbend from his duty. But I’d come to see he was a man like any other, with the same weaknesses and needs, and the secret to luring him off course might be found in his frailty, and not his strength.

15

It was the afternoon of the day of the Lovefeast. I was bent over the table, up to my elbows in flour, taking out my grievances on the dough by kneading it with a murderous passion. Tegen was at her loom and Mamm snoozed in her chair.

Tegen left her needle fixed between the warp strings for another day. ‘Well, I’m beat,’ she said, slumping in her chair. ‘We’re doing more work than we ever belonged to do these days.’

‘Aye, and good work is kept from us. It’s because of me being made Sunday school mistress. We’ve rarely had to go shrimping other years, and when did we ever resort to filling a cart with sand to sell to the miners so they can sprinkle it on their floors?’

‘I’ve even tried cutting griglans on the heath and making brooms with them, but nobody would buy them from me,’ said Tegen, yawning and giving her arms a stretch. ‘I wish you’d sing like you used to on baking days. It used to cheer me.’

‘I daren’t sing with all my enemies waiting to catch me out in some sin.’

‘I do hear things, tittle-tattle. You should talk to Tobias Hawkey. He’ll speak out against any mischief. He’ll be parson once the chapel’s built and the minister’s gone back to Newlyn, and he’s well thought of hereabouts.’

‘I don’t care for the man’s home-spun sermons,’ I said, pushing my rolling pin over the dough.

‘Well, I do,’ she said. ‘It was when ’Bias began leading the prayer meetings that I saw the light.’

Realising what she meant, I let go of the rolling pin. ‘You’re not telling me that you’re under conviction, Teg?’

‘I can’t deny it. But I don’t want it shouted from the rooftops. Is it too much to believe a day will come when hard work and sober living get their just deserts, as ’Bias says they should? I believe there’ll be a reckoning at the Last Judgement. I’d like to see those cormorants who blacken your name standing before the Throne of Mercy when their time comes. God forgive me, I know that don’t show Christian mercy.’

We were quiet a moment. Buttery light streamed in from the open top half of the front door, flour dust swirling in it. Outside, swallows were swooping down under the eaves to feed their chicks, and the air was alive with their screech

ing cries.

‘Suppose you offered to share the burden of the teaching with Loveday?’ said Tegen.

‘Share the teaching with her? I’d die first,’ I said, slapping a fresh ball of dough onto the table.

‘Grace and the bettermost think Loveday should be teacher, by rights.’

‘Loveday’s got Johnenry back, ain’t that enough for her?’

‘Oh Mary, at least stay away from the Lovefeast tonight, I pray you.’

‘I won’t be told where I can go and where I can’t. I’ve done no wrong. I’ve barely set eyes on the minister for weeks now. I am the school mistress. It’s my place to be there.’

‘Look at you. Thin as a rush light. I swear there’s no more fearful sight than a woman over-gone on a man.’

‘What makes you say such a thing?’ I cried.

‘I’m your sister. You can’t hide things from me.’

She looked me in the eye for a moment, and I realised she knew me better than I’d thought.

‘Well, you needn’t go worrying yourself,’ I said, going back to my baking. ‘The minister ain’t after me. Last time we met he tried to pawn me off on Johnenry.’

She shook her head. ‘Poor Johnenry,’ she said.

Hell or high water wouldn’t have kept me away from the Lovefeast. Tegen and I got there late. As we came through the door, I saw Gideon up in his pulpit. He looked up, saw us there, and took a deep breath.

‘Welcome, sisters,’ he said. ‘Your friends and neighbours will make room for you on the benches. We are listening to a short reading from Matthew.’ He found his place and began to read.

All the women were huddled together on one side, while across the aisle the men had plenty of room on their benches. Tegen tried to sit with the row of poorer women underneath the hissing and smoking tapers, the grease running down the walls behind them, but I pulled her away. We squeezed ourselves onto one of the women’s benches. When we were settled, I glanced about me. The barn had never been so packed. There were new faces, people without clothes decent enough to go to the usual weekday prayer meetings. I was taken aback to find Nathaniel Nancarrow on the men’s benches, and nudged Tegen to let her know. She turned pink from her neck to the tips of her ears. A double-handled mug filled with black tea was passed along the bench to me, and then a plate of bread and saffron buns. But I had no stomach for either food or drink.

It was then I saw the old woman in a mob cap and black dress who was sitting on the front bench. It was the first time that Aunt Madgie had shown her face at one of Gideon’s meetings. She turned her head and her withering glance sent a shiver through me as I looked away. Her daughter Grace Skewes was alongside her. On the end of the row was Grace’s daughter, Loveday, wearing a dress with wide shoulders and leg-of-lamb sleeves. She was simpering at Johnenry, who sat opposite her on the men’s bench.

Gideon had stopped reading. I looked up to find him gazing out at the hearers. He read the next lines more slowly, looking up often, so we’d take note of the words.

‘A good man out of the good treasure of the heart bringeth forth good things: and an evil man out of the evil treasure bringeth forth evil things.

‘But I say unto you, That every idle word that men shall speak, they shall give account thereof in the day of judgement.’

I fell to wondering what the lines meant. Soon after, the reading came to an end, and he spoke to us in his own words.

‘I see new faces here this evening. You are all greatly welcome. We have bread, tea, heavy cake, enough for all. Consider for a moment what has brought us together at this Lovefeast – especially in the light the gospel text from Matthew. What, indeed, do we mean by “Lovefeast”? It is an occasion to come together with our neighbours in a spirit of harmony and trust, to celebrate the bonds of friendship and love between us. Let us put aside petty rivalries and forget past grudges in a spirit of open trust.’ Some turned and smiled at their neighbours, while others stared into their laps. ‘In recent weeks it has come to my attention that I, myself, have not altogether escaped suspicion, and have even been the object of censure.’ Murmurings spread along the benches at this. ‘I assure you all that my motives and conduct since I first arrived in this cove have at all times been honest and true. I am no saint. I have acknowledged at previous meetings that I have trespassed in the past, and we must ever be on our guard against temptation. In the same wise, I urge you to forgive your neighbour’s transgressions. Remember the words of John: He that is without sin among you, let him first cast a stone at her.’ At that, Loveday turned her head and looked straight at me, but I held her gaze.

‘I bid you to forswear idle tattle and to look to your own sins before casting stones at others,’ said Gideon. ‘Very soon all our hard work to build a chapel in this cove will come to fruition, and I will be gone from your midst. You will be in good hands with Mr Hawkey. Now, who among you would like to speak of their spiritual experience this week?’

Right away, I stood up and made my way to the aisle. I walked towards the communion rail, head held high, even though my legs trembled under me. For all I shook, I meant to put a stop to the whispering I knew was going on behind my back, and was hell-bent on taking this chance while they were all together under one roof. A hush fell over all as I halted at the rail, before turning to face the hearers.

‘Is it right that a woman should stand at the communion rail to testify?’ shouted old Thomas.

‘It is only a wooden rail,’ said Gideon. ‘Sister Blight is welcome to stand and testify wherever she so wishes – and so may any other woman or man present.’

‘Dear friends,’ I said. ‘It is wonderful to stand here and feel God’s divine love in this room.’

‘Praise the Lord!’ shouted a coarse woman at the back.

‘Old enemies are now become friends,’ I said. ‘Who would have thought it could be so, a few months back? I used to scoff when people said “One and All!” But now I’m beginning to believe it, sisters and brothers.’

‘God grant it,’ shouted old Thomas.

‘Hosanna in the highest!’ called another man.

‘But there’s still strife between us women, isn’t there? Work is kept from me, and from my sister. Black lies have been spread around this village.’

A rumble was heard down on the front bench where the bettermost sat. ‘What are you saying of, Sister Blight?’ cried Grace Skewes. ‘Who are you pointing the finger at?’

‘Sister Blight,’ said Gideon. ‘May I ask you to restrict your testimony to a declaration of what God has done for your soul since last we met – and to refrain from accusations about your neighbours.’

‘I have been blessed these last few weeks, teaching the Scriptures to children, the little ones of some of you here,’ I said, without turning to look up at Gideon. ‘The children were willing to learn at first, but it seems as though a few of them have been given the wink to play up.’

‘Shame! Let Mary be teacher, if she so wishes,’ cried a woman. It was Martha Tregaskis, flushed with liquor, her nose red and swollen.

‘I ask if there will ever come a time when we can love our neighbour as we love ourselves,’ I said. ‘As King Jesus told us to, instead of scheming to keep each other down?’

Grace Skewes stood up, and called to Gideon. ‘Are we to listen to a sermon from a woman?’

‘I am only a woman and know it’s not proper for me to take a gospel text,’ I said.

Gideon broke in on me. ‘Sister Blight, I think you have had your say,’ he said.

Grace Skewes sat down again and she and her neighbours put their heads together, mumbling. The rougher sort of women in the back rows were growing fractious.

‘Come now, brothers and sisters, we are in accord, at least in all essentials,’ said Gideon. ‘So let’s remind ourselves why we are here. If there are misunderstandings, then let us speak honestly. It will do no good if we shrink from one another or allow resentments to fester and grow into hatred. Thank you, Sister Blight, for raising t

hese matters. Now, who else would like to exhort?’

I stepped away from the rail and walked briskly down the centre aisle. It was so quiet I could hear the rustle of my skirts and the beat of my heart. When I got to the bench where I’d been sitting, the women there would not look at me or make way to let me in, so I went on until I reached the back of the barn. I was riled and wanted to spite them all, so I strode towards the nearest empty bench on the men’s side and sat down. Someone at the front gasped, and snide whispers spread around the benches. I looked straight ahead of me, pretending not to care.

Hearing a great sigh, I turned to see women fussing over one of their neighbours on the crowded benches opposite. ‘It’s Aunty Merryn. She have fainted!’ someone cried.

‘It’s no surprise, the way we’re all packed in like pilchards, scarce able to breathe,’ another woman said.

‘Such foolishness!’ said young Cissie Olds, as she stood up and pushed her way along her bench to the aisle. She came across and sat next to me. The Widow Chegwidden and another woman followed her.

‘Yes, come along, there is space for all,’ cried Gideon. ‘We don’t want women swooning because of quaint notions of propriety. Move across to the men’s benches, if you will!’

‘Have you lost your senses, parson?’ cried old Thomas.

‘I know of no commandment that says men and women shall not share a bench,’ said Gideon. ‘Didn’t the Almighty place men and women in the Garden to work in harmonious partnership? Remember what the Apostle Paul said: there is neither male nor female, but all are one in Christ Jesus.’

Hearing this, Nancy Spargo moved across, with a couple of her friends in tow, although they looked less than sure about it. They sat on the bench in front of us. Before long, perhaps ten women had crossed the divide, while the men watched, aghast. I found myself sitting alongside four or five women, and with each new arrival I was forced to slide a little further along the bench.

Wrecker

Wrecker