- Home

- Noel O'Reilly

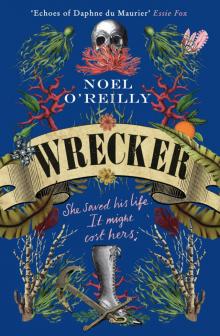

Wrecker Page 23

Wrecker Read online

Page 23

When I opened the kitchen door I was near deafened by the rowdy voices of the children, who stood in little groups around the room, pushing, shoving and teasing one another. With horror, I saw that Thomas Penpol and Kit Trefusis were there. They knew I’d been in the church with Gideon, and I was sure they must have passed it on to the other children.

‘Quiet! I demand silence right this minute,’ I shouted. The children carried on, heedless, but I could tell they had heard me. ‘Shut your mouths this minute, every one of you!’ I cried. ‘Do you hear me?’ I took up the stick that lay upon the dresser. ‘If you do not do as you are told, every last one of you will get a stroke of this on both hands.’ My voice was high and strained, and I knew I showed more fear than mastery. Aunt Madgie’s vile catechisms were spread all over the table. I picked them up and handed a pile to the child at each end of the table to pass along to their classmates. All the while, I felt the old witch listening and ill-wishing me behind the door.

Once I’d taken my place in the chair at the head of the table, I set the stick down before me and began reading aloud from the catechism. The children listened in silence to the fate that awaited them in Hell. My nerves were as frayed. After about a quarter of an hour, I felt calm enough to look up at them.

‘Please, Sister Blight,’ said Kit, putting his hand up.

‘What is it, Kit?’

‘I need a piss.’ Every boy and every girl broke into giggles, except poor Sarah Pengilly, the class monitor. I picked up Aunt Madgie’s stick and slammed it down on the table so hard that the wood split. I put the bent stick down again, and looked from face to face, fighting back tears.

Kit smiled sneakily at his mates. ‘Sister Blight, what do harlot mean?’ he said.

Sarah gasped, and looked up at me. The others looked at each other, but weren’t bold enough to glance my way.

‘What do it mean, Sister Blight? Do it say in here?’ said Tom Penpol. He waved his catechism and looked to the others for backing. They were in uproar by now, Kit and the other boys patting Tom on the back to spur him on. ‘Kit’s big brother says you should know,’ Tom said, sniggering.

I got to my feet and took up the broken cane, twisting the end until it snapped off, and throwing the shorter piece onto the table. Tapping the stick on my palm, I glared at Tom Penpol.

‘I won’t have you speak to me this way,’ I said. ‘Come over here.’ Tom climbed over the laps of the others, making a meal of it, and came to stand before me with an impish smile on his face to show he wasn’t afraid. But he had turned fearfully pale.

‘Hold out your hand,’ I commanded. Tom wiped the spit off his chin with the back of his hand. He wasn’t laughing now.

‘The stick be broke, Sister Blight,’ he said, with a sniffle.

‘You dursn’t hit him with that custiss, Sister, he will get splinters,’ said Peggy Combelleck.

‘Keep your hand steady, boy,’ I said, raising the stick.

He put his hand out with the fingers curled a little, and he flinched as I raised the stick higher still. Closing my eyes, I brought the stick down — more smartly than I meant to. I must have missed his palm and hit him across his little fingers, because I heard the wood strike bone. He whimpered and his hand shot into his armpit. He screwed his face up tight, and a tear rolled down his cheek.

‘I’m going to fetch my Mamm,’ he bleated, breaking into a sob. ‘She will bring her rolling pin and give you what for.’ He slipped past me and ran to the door, opened it and dashed down the hallway. Out in the hall, the front door creaked on its hinges and slammed shut. The other boys were already climbing out from the form and running after him. The girls hesitated, then followed the boys out. Only my little friend Sarah Pengilly was left, trembling in her seat.

I went into the hall and right away heard the old woman’s crook striking the floor as she loomed out of the shadows of her house. She blinked as she entered the hall. The children had left the front door open and let in a shaft of dusty light. I was in a hot temper and the sight of her only kindled it the more.

‘Are you content?’ I said. ‘I have tried your way and this is my reward for it. A mutiny.’

‘You were never equal to the position,’ she said. She spoke calmly, with only the slightest hint of a taunt in her voice.

I took a step closer to her. ‘You have brought me to this. You have connived to bring me down.’

‘You have brought this on yourself, my lady. It is not my doing.’

‘You think you can stand in judgement over me,’ I said.

‘The Almighty will judge you, not me.’

‘He will judge you too.’

‘I have no fear of the Redeemer’s judgement.’

‘If you are as pious as you pretend, then why do you never round on your neighbours when they breach the Sabbath?’ I cried. ‘How is it that you sanction wrecking and smuggling? Your notions of right and wrong are a pretty puzzle, I seem.’

‘The people’s livelihood comes before all else,’ she said, holding my gaze steadily.

‘The Almighty will see into your heart on Judgement Day, and call you to account for the lies you’ve told.’

Her eyelids drooped and she began to recite some scripture under her breath. ‘Yea, all will know thy base cravings, thou agent of perdition. The Lord will punish the haughtiness of the daughters of Zion who walk and mince as they go, with stretched-forth necks and wanton eyes. Isaiah 3:16.’ She quaked, like one possessed by demons. ‘He will uncover thy secret parts, and instead of beauty there will be branding.’ Only the whites of her eyes showed under her eyelids, as if she looked backwards into the darkness of her own soul.

‘Listen to yourself. You are mazed with bitterness and envy,’ I said. ‘An ill-wishing, cold-hearted witch. A false old relic whose time is nearly past.’

Her eyelids began to quiver, then she struck me hard across the face. I tasted blood, and my fingertips dripped red when I took them from my mouth. Before I could stop myself, I’d slapped the old devil back with all my might. Her crook clattered to the floor as she staggered backwards, cracking her head against the wall. For a moment she didn’t move, her head on one side, her gaze downwards. When she spoke it was in a thin rasp.

‘I saw you on the beach that day. I know you did it.’ She tried to lift her chin to look me in the eye, but couldn’t. ‘You want me dead to stop me standing before the Magistrate.’

‘I did no more than steal a pair of boots,’ I whispered, putting my mouth close to her ear.

‘You bit that lady’s earlobes off to get your grubby hands on her jewels.’ She slid further down the wall as she spoke. ‘To inform against such as you would be . . .’ Her eyes closed as she slid onto the floor. There was a smear of red down the wall behind her.

I put my fingers to her neck and felt for her pulse among the folds of wrinkled skin. Her lifeblood throbbed slowly, the merest twitch under my thumb. What would befall me when she came round? The old woman was weak, and it would have been easy enough to put my hand over her mouth and snuff the life out of her once and for all. It was no more than she deserved, but I could never have brought myself to do it.

I looked up and down the hallway, and saw little Sarah Pengilly standing alone by the kitchen door, watching me and fumbling with her apron.

‘Don’t fret, now, Sarah. Aunt Madgie has taken a fall. Will you fetch the Widow Chegwidden to look at her? And let her kin know she’s had an accident and hurt herself.’

The girl nodded her head quickly, and moved down the hallway, pressing herself against the wall to keep clear of me as she passed.

A moment later I heard one of the boys shout out in the lane, ‘It’s the gallows for ’ee now, harlot!’ Then his feet pattered into the distance.

I wasted no time in running home, picking up my basket, and rushing up the hill to the headland. Huge black clouds churned and raced across a vast sky. When I saw the church ahead of me I felt a tremor of unease, but I pushed on and stepped into the dark bui

lding. I put my basket down, and sat in a pew, shivering in the draught. I looked over my shoulder at where the bell ropes hung under the tower, half expecting to see Gideon standing there. The church had seemed enchanted on that other morning, but now it was dark, drab and dirty. I thought of the hour I’d spent with Gideon lying under the tower and a faintness came over me.

It was a good while before I heard the distant sound of the bell in Paul tolling the hour. It set my heart thumping. He would come now, surely he would. I waited a while longer, then, impatient and uneasy, walked out of the church. Heavy rain had begun to fall. I went through the porch into the graveyard, my feet sinking into the soggy turf, and peered beyond the dripping trees. There was nobody to be seen. I could hear a distant rumble of thunder, a storm rolling in off the Atlantic.

I went back inside and waited, shivering in a creaky, worm-eaten pew, water dripping over the stone flags from the hem of my skirt. Doubts bred in my mind like rats in a cellar. As the long minutes passed, and lengthened to hours, my mood shifted from frantic hope to despair and at last to a kind of daze. The light was fading and the church falling under deeper shadow. It would be dark within the hour. The roar of the tempest grew louder as each moment passed, and now and then a flash of lightning lit up the church. He was not coming.

I pushed hard on the church door to get it open, and the gale slammed it shut behind me once I’d left. Up on the tower the leering granite crone squatted and held her gaping kons open with her hands, a torrent of rainwater gushing out her and falling onto the stone cross that lay beneath. The cross had toppled and now lay flat on the earth, broken in two. A high wind was at my back, whipping in off the sea and blowing me this way and that. Gulls were sent shooting pell-mell over the cliff tops. Before long, I was wet through with freezing rain. Below me, the grey sea raged, and tall waves rolled in from afar. A gust knocked me onto all fours, and when I got up, I found I could lean back against the gale with all my weight and the wind stood me upright. In that instant, there was an almighty thunder clap overhead. The earth shook under my feet. An eerie glow lit the sky as it was rent by flashes of jagged white lightning, and the air smelt scorched. I ran wildly down the steep bluff until I reached the street of blackened miners’ cottages, which at least buffered the wind. At last, I turned onto Downlong Row and ran into the cottage.

I dragged myself up the stairs, my wet clothes weighing me down. I took them off and dried myself as best I could. I caught sight of myself in my frayed white shift in the rusty oval looking glass in Mamm’s old room. It was like seeing a ghost. A shirt hung out of a drawer, so I seized it and threw it over the mirror. Then I went back downstairs, tossed my wet clothes in the laundry tub, mopped the floor, and sat at the table. I was all alone. Tegen was looking after Nathaniel’s children while he sailed to Marazion to visit his sister, who was poorly.

As the stillness and quiet of the cottage settled about me, I saw everything as it really was, naught but lies and falsehood. What a fool I’d been! Gideon Stone wasn’t the man I’d dreamt he was, but an adulterer, a canting, cowardly liar, a drunkard, a stone picked up at the tide’s edge that sparkled when wet, but when dry showed itself to be as drab as any other pebble on the beach. I went into a blind rage, beating the wall with my fists till I could bear it no more, throwing the metal pail across the kitchen. Still my anger hadn’t abated, so I took fistfuls of my hair in my hands and tried to tear it out by the roots.

Weary and beside myself, I dropped onto a chair at the table, and let the angry tears flow. I thought my grief would never end, but after a hundred shuddering sobs I became quiet. I laid my head down on my arms and fell into a heavy sleep. When I awoke, it was night.

21

I sat in the kitchen in the dim amber glow of a rush light. The storm had moved off over the moor and a hush had fallen over the village. Every rustle in the thatch, every buffet of the window unnerved me. I heard a cough outside and near jumped out of my skin, but I told myself it was just a neighbour passing by in the lane. A moment later there was a snigger, so I went and stood with my ear to the door. After a while there was a knock, then two more loud raps on the door, and next a horn blasted so loud that it could only have come from one of the seiner’s speaking trumpets that the fishermen used out on the water. It must have sounded right outside the door. A fearful rantan of drumming and shouting began. Peeking out of the window, I saw my neighbours out there shouting and jeering, beating kettles, pans and tea trays, while others blew whistles and horns. They sounded like a hunting party of lunatics. It was a long while before the din came to an end.

In the quiet that followed, I heard a woman ask, ‘Who is it this time?’

‘That ginger hussy,’ said another. ‘A bad turn out she is, needs taking in hand.’

‘She stole Loveday Skewes’ man when they was all but at the altar,’ called another voice. ‘And she turned the minister’s head too, afore that.’

‘I know the wench. A cheat and a scold, and proud as Satan. Give a woman like that her head, and soon she’ll have the whole village by the heels.’

‘She tried to murder Aunt Madgie, I knows that for a fact.’

‘And they say she be the cannibal?’

‘Aye, and the rest of we has been tarred with the same brush. We’ve never had so many Preventive Men crawling over the village as in these last months. I hope she hangs for it.’

There was another bang on the door, and a call for me to show myself. I had no choice but to face them, so I opened the door and stood on the threshold. The little courtyard was packed to the gunwales with sneering neighbours, and as soon as I showed myself they began jeering and cursing. Betsy Stoddern was to the fore, but there was no sign of her mate Loveday Skewes, even though she’d surely put them all up to it.

‘That’s enough now!’ I cried when there was a lull in the shouting. ‘You should be ashamed of yourselves, tormenting a lone woman.’

‘How do we know you be alone?’ said Betsy. ‘For all we know, you might have one of your fancy men inside.’

That got them shouting again, so I had to wait before I could speak. ‘You’ve had your sport,’ I said. ‘Most of you hardly know me. What right have you to judge? Go home now, all of you.’

‘Don’t be uppity with us, madam!’ said Betsy.

‘How many men you got in there?’ shouted some idle fellow, to screams of laughter.

With horror, I saw that huge lummox Pentecost barging his way through the throng towards me, towering over the others. As he got closer I saw his tiny eyes, his bent nose with its patchwork of breaks and his pocked slab of a chin.

‘Don’t you dare lay a finger on her!’ shouted a woman at the back of the courtyard. I knew that voice – it was Cissie Olds. So at least I had one friend. But Pentecost had already got behind me and thrown his huge arms round me, pinning my arms to my sides. He lifted me as if I weighed no more than a cloth doll. As my feet left the ground, I back-kicked him with all my might but to no avail. He carried me towards the alley that led onto Downlong Row, the crowd parting to let him pass. I couldn’t bear the filthy looks they gave me. We reached the alley and the big fellow could hardly fit inside, having to stoop to get me through. I heard a donkey braying at the other end, and I knew then what was in store for me. There was to be a Riding, and I was the one to be shamed.

Pentecost carried me out of the dark tunnel into the torchlit lane. I was too frantic to take it all in, faces all around me looming out of the dark, piercing shouts and laughter. He hoisted me above the heads of the rabble and threw me onto the hard floor of a donkey cart. It stank of hay and rotten apples. Cissie Olds got a knee onto the cart and tried to climb in after me. ‘Let her go, you devils!’ she shouted, as she was pulled off and dragged away. The cart jolted on its way and lurched from side to side as the jittery donkey pulled me slowly down the steep hill. I huddled in a corner, holding my knees to my chest, trying to hide my face, while my neighbours pelted me with potato peels and rotten eggs. Young lads le

apt up to spit at me, and women, flushed with drink, threw back their heads and roared with laughter.

My rush of panic slowed to a deep dread, as I picked out the faces of neighbours, young and old, filing behind the cart, some carrying horn lanterns aloft, putting the thatch at risk. The mood was like Christmas Tide or when the fair comes to Penzance. Children had been taken from their beds to see the show. Billows of bitter smoke blew into my face, half blinding me and making my eyes stream.

When we reached the quay I heard raised voices, men reciting lines in the way of actors in a Mummers’ Play. I couldn’t catch their words but there were bursts of laughter from those who’d gathered to hear them. Three large effigies were mounted twenty feet in the air on high poles, down at the western end of the harbour. The crowd was more scattered down there, and as the tide was out some had climbed down onto the sand to dance around a great bonfire that blazed there. The cart was led to the front where space had been cleared for it under the effigies. I was jerked and bumped about as the nervous donkey started at every sudden loud bang.

Closer up, I saw who the tall effigies stood for. One wore a dress with straw stuffed up the sleeves and poking out of the cuffs. She had long orange locks made of yarn that hung almost to her feet. The others were men, and Gideon was so like the real man that nobody could fail to know whom it signified. The last was surely meant to be Johnenry, as he had a miner’s stoop on his head. The men who held the poles and spoke for the effigies wore masks with horns and big gaping mouths, horrible in the murky light as they leered out of the shifting smoke. The one who held up the effigy that was meant to be me, jiggled her about and spoke in a high-pitched, snot-nosed voice.

‘Oh, come closer to me, minister, so I can feel the Holy Fire!’ he said.

Wrecker

Wrecker